ISB's Dr. Mary Brunkow Wins 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine

The prize recognizes foundational discoveries about regulatory T cells and the FOXP3 gene that redefined immune tolerance and opened avenues to treat autoimmune disease, enable transplantation, and advance immuno-oncology. ISB celebrates Dr. Brunkow’s leadership and collaborative science.

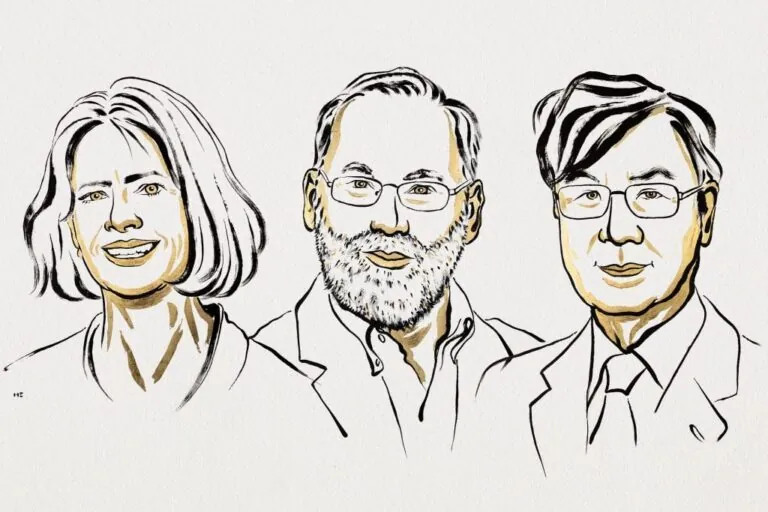

The Nobel Assembly at Karolinska Institutet has awarded the 2025 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Drs. Mary E. Brunkow (Institute for Systems Biology), Fred Ramsdell, and Shimon Sakaguchi.

“ISB congratulates Dr. Brunkow on this extraordinary honor and celebrates her contributions to science and human health,” said ISB President Dr. Jim Heath. “Her work transformed how we think about the immune system.”

The trio was recognized for discoveries that revealed how the immune system achieves peripheral immune tolerance — including identifying regulatory T cells (Tregs) and the central role of the FOXP3 gene in their development and function. Their work reshaped modern immunology and opened new paths in autoimmune disease, transplantation, and cancer immunotherapy.

The researchers’ foundational discoveries answered a century-old riddle: Why doesn’t the immune system attack the body’s own tissues? Brunkow and colleagues established FOXP3 as the molecular key to regulatory T cells, the gatekeepers that temper immune responses and prevent self-destruction.

When Sweden Calls, Go Back to Sleep

Brunkow learned of the Nobel in unforgettable fashion. In the early hours of October 6, calls from Sweden lit up her phone — twice. Assuming spam, she muted the device. Minutes later, around 3 a.m., a photographer from The Associated Press knocked on her door.

After some incredulous back-and-forth through the window and a glimpse of the official press release, the news landed: Mary Brunkow had won the Nobel Prize.

“The last 24 hours have been amazing, overwhelming, and exciting,” Brunkow said at a press conference held at ISB on October 7. “At first I thought it was an elaborate scam — but then I spoke with the Nobel Committee. It began to sink in.”

A Puzzling Mouse, FOXP3, and Tregs

The roots of the prize trace to Seattle-born biotech company Darwin Molecular, where Brunkow led a team integrating mouse genetics, genomics, and DNA sequencing — a bold approach in the pre-genome-browser era.

Working with colleagues at Oak Ridge National Laboratory, Brunkow and her team studied an unusual mouse known as scurfy, which developed a severe, inherited immune disorder. Their investigation revealed that the disease was linked to the X chromosome. Through careful breeding and genetic sequencing, the researchers discovered a tiny two-base-pair deletion in a previously uncharacterized gene, later named FOXP3. This discovery uncovered a critical genetic switch that helps the immune system maintain balance and avoid attacking the body’s own tissues.

In parallel, Ramsdell’s immunology group dissected the cellular consequences. Together, the efforts linked FOXP3 mutations to the loss of a regulatory T-cell program that restrains immune attack.

Crucially, the work bridged to humans. Mutations in FOXP3 cause IPEX syndrome, a devastating pediatric autoimmune disorder, cementing FOXP3 as a master regulator of immune tolerance.

“Mary’s discovery provided the molecular mechanism behind a long-debated concept,” Heath said. “Once FOXP3 marked regulatory T cells, the field could advance at pace, touching virtually every area of human health.”

From Discovery to Impact

The FOXP3/Treg axis continues to influence medicine on two fronts:

- Releasing the brakes in cancer: Tumors often recruit Tregs to suppress anti-tumor immunity. Insights stemming from the FOXP3 pathway inform strategies that lift suppression so the immune system can attack cancer.

- Applying the brakes in autoimmunity and transplantation: Treg-based or Treg-tuning therapies aim to prevent graft-versus-host disease and quell autoimmune flares, promoting tolerance where it’s beneficial.

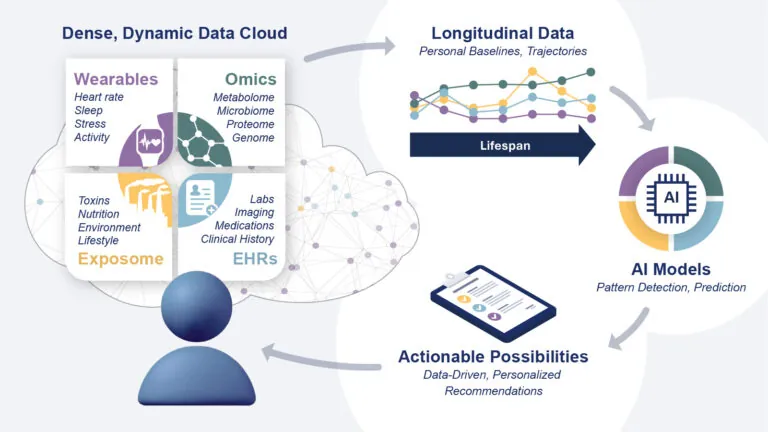

At ISB, those ideas dovetail with programs that connect fundamental biology to real-world health, from long-COVID immunology to population-scale microbiome and genomics efforts — many accelerated through ISB’s alliance with Providence.

“Basic discovery is the lever arm that changes the world,” Heath noted. “Out of this one discovery comes a whole industry of ways to target and tune the immune system.”

Brunkow, who joined Darwin Molecular in 1994, began the FOXP3 journey in 1995 and published its seminal description in 2001, reflected on the team ethos that powered the work: “It was an awesome time and an awesome team. We knew we were doing something important.”

As attention turned to Stockholm in December, she remained characteristically humble — and optimistic — about the future of science.

“Federal support has been vital to progress in medicine and basic science,” Brunkow said. “Even in uncertain times, determined optimism is how we move forward.”